Derived from the ancient Sanskrit word “yuj”, the definition of yoga is commonly translated as “to yoke”. From there, the interpretations of what is being yoked and why vary depending upon school of thought and intention. It is understood the original mention of yoga in the Rig Veda (approx. 1500-1200 BCE) was referring to the yoking of horses, as in the Hindu sun god Surya in his chariot being pulled by seven horses.

The invention of yoga cannot be ascribed to one individual though Patanjali is credited with compiling the Yoga Sutras (approx. 400-500 CE). This text is a collection of ideas and philosophies from various traditions organised into a system which focuses upon behaviour and disciplining the mind. Patanjali’s commentary on postures was limited to practitioners finding a comfortable seat which has been interpreted both literally and figuratively. The physical practice (asanas) as we know it today has been under investigation by historians and scholars such as Anya Foxen, Ida Jo, Stefanie Syman, and Mark Singleton, though not all share comparable attention from the yoga community at large. Research discussing yoga’s foundations in female physical culture are of particular interest to me though much of it may remain speculative given women’s frequent absence from historical archives.

For those seeking yoga’s spiritual offerings or those who argue for nationalistic exclusivity, it is important to recognise yoga was not founded solely upon Hindu beliefs. The philosophical amalgamation includes Buddhism and Jainism. What binds them all together is the thread of patriarchy which is worth reflecting upon when considering how it influences yoga’s practices, values, and structures including unquestioned authority, gendered hierarchy, and sectarian concepts of purification and pollution.

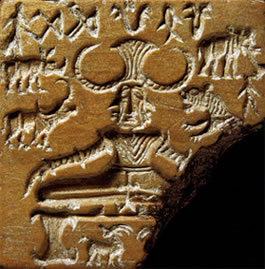

In an effort to validate (and sometimes mystify) contemporary yoga, there are those who claim the physical practices are from the Bronze Age. An ancient artefact unto itself, such as the Pashupati Seal shown here (approx. 2,300-2,000 BCE), does not offer conclusive evidence of a systematised physical practice or ritual discipline; the human body has a finite capacity of articulations and the pictorial context can only be guessed at. It is because these representations are susceptible to cultural interpretation, doctrinarism, and fundamentalism they have been used as ‘evidence’ of early yoga practices. The asanas we are familiar with today have only been adjudicated over roughly the past 100 years though their obvious affiliations with ancient classical Indian dance are an area I will be studying in the future.

What all of this means for practitioners is that it’s irrelevant if you can perform acrobatic feats on a mat. Yoga has a complicated, controversial, and multi-cultural history pursued by academics and amateurs alike. My advice is to learn as much as you can from as many sources as you can with your eyes wide open and a keen awareness of human fallibility.